Anchoring Bias occurs when decisions are based on the first data point, graph, or image that we encounter. Our brains are hardwired to rely too heavily, or anchor, on one trait or piece of information, typically the first piece of information we acquire on that subject. As a result, that anchoring idea, number, graph or image becomes the basis for our decision. Anchoring Bias is the source of the power of first impressions. The blindspot with this bias lies with Inaccurate anchors that are used deliberately by others to shape public opinion, influence product decisions, and guide behaviors. We see this use of Anchoring Bias in advertising, marketing or negotiations. For example, in a negotiation, the first number offered becomes the anchor. Knowing this, a salesperson might deliberately set the anchor too high (as in the price of a car) so that any future decrease in price will seem like a discount.

Nobel prize winning economist Daniel Kahneman and his colleague Amos Tversky were the first to theorize about Anchoring Bias. In one experiment they divided people into two groups. The first group was asked these questions:

- Is the height of the tallest redwood more or less than 1,200 feet?

- What is your best guess about the height of the tallest redwood?

The second group was asked these questions:

- Is the height of the tallest redwood more or less than 180 feet?

- What is your best guess about the height of the tallest redwood?

The average of the first group’s answers was 844 feet while the second group averaged 282 feet. (The tallest redwood is 380 feet.) The anchoring piece of information skewed the results in each group. Kahneman and Tversky showed that Anchoring Bias can occur even when the anchor is not related to the task. In a different experiment, people watched a roulette wheel that was predetermined to stop at 10 or 65 and then were asked to guess the percentage of African countries in the United Nations. The anchor of the roulette wheel impacted their answers.

J.C. Penney learned the impact of Anchoring Bias the hard way. They changed their pricing from frequent sales and discounts to lower prices without discounts. Having lower prices without discounting would help them control their inventory, save floor staff from constantly repricing and give lower prices to consumers. It would be a win-win for everyone. But it wasn’t. J.C. Penney’s sales fell 25% and they soon switched back to coupons and sale prices. Why did this happen? It was Anchoring Bias. Consumers did not believe that the lower price was a good value. Without clear knowledge of what something should cost, we rely on the first available point to tell us. Seeing that something was $40 but is now 25% off feels like a better value than the same item always priced at $30. Even when consumers could see that the “no sale” price was the same or better than the “sale” price, they did not believe it.

Anchoring Bias can easily lead to harmful social and institutional biases. The Beauty Myth is but one example of how this occurs. The Beauty Myth (Naomi Wolfe) posits that as women have risen to higher social and professional standing, they have been subjected to a narrow unrealistic social standard of beauty, resulting in all types of behaviors to meet the unreachable standard, including specialized procedures, creams or clothing for every part of the body. This particular cognitive bias is present in many types of gender bias and is institutionalized in a $89 billion dollar cosmetic industry. In this case, the anchor for a woman’s physical appearance is set at a place that few people could achieve and the anchor in nearly every case is irrelevant to job performance.

Mitigating Anchoring Bias is challenging, and like most of the other cognitive biases we have discussed, it requires stopping and taking time. First, we must recognize that we are in the middle of a decision-making process and get ourselves out of the loop of unconscious decision-making. Then we must take time to question the source or credibility of the data point, graph or image by asking:

- Is this information relevant to the decision I am making?

- Is it coming from an independent source or from someone who has a vested interest in how I decide?

- What is the context of this information? What is the “standard” I am holding in this decision?

- What do I already know about this topic?

Better yet, when we know we are entering into a potential negotiation or purchasing situation, we should research ahead of time to determine what is the correct anchor for our decision. When possible, we should also examine our own accepted “norms” to see if they are based on an irrelevant and potentially harmful anchor.

If you have a brain, you have bias!

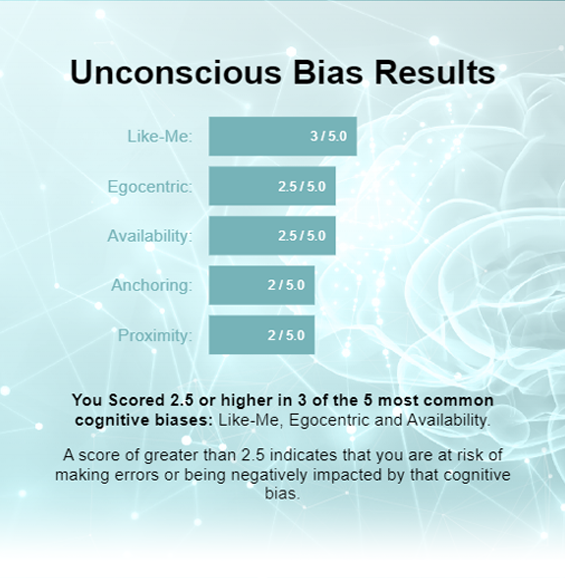

This 20-question test provides actionable insights. Select the response that closely matches your current state of mind. The design is intended to introduce you to the five most common cognitive biases: Like-me, Egocentric, Availability, Anchoring & Proximity. Results may vary. No data is shared with anyone.

Percipio Company is led by Matthew Cahill. His deep expertise in cognitive, social, and workplace biases is rooted in the belief that if you have a brain, you have bias®. He works with executives to reduce mental mistakes, strengthen workplace relationships & disrupt existing bias within current HR processes, meeting protocols and corporate policies. Matthew has demonstrated success with large clients like LinkedIn, Salesforce and dozens of small to mid-size companies looking to create more inclusive workplaces, work smarter, generate more revenue and move from bias to belonging®.